Rincon Coast Seawall History

Rincon Coast Seawall History and Design

Article by Chuck Menzel

June 2023

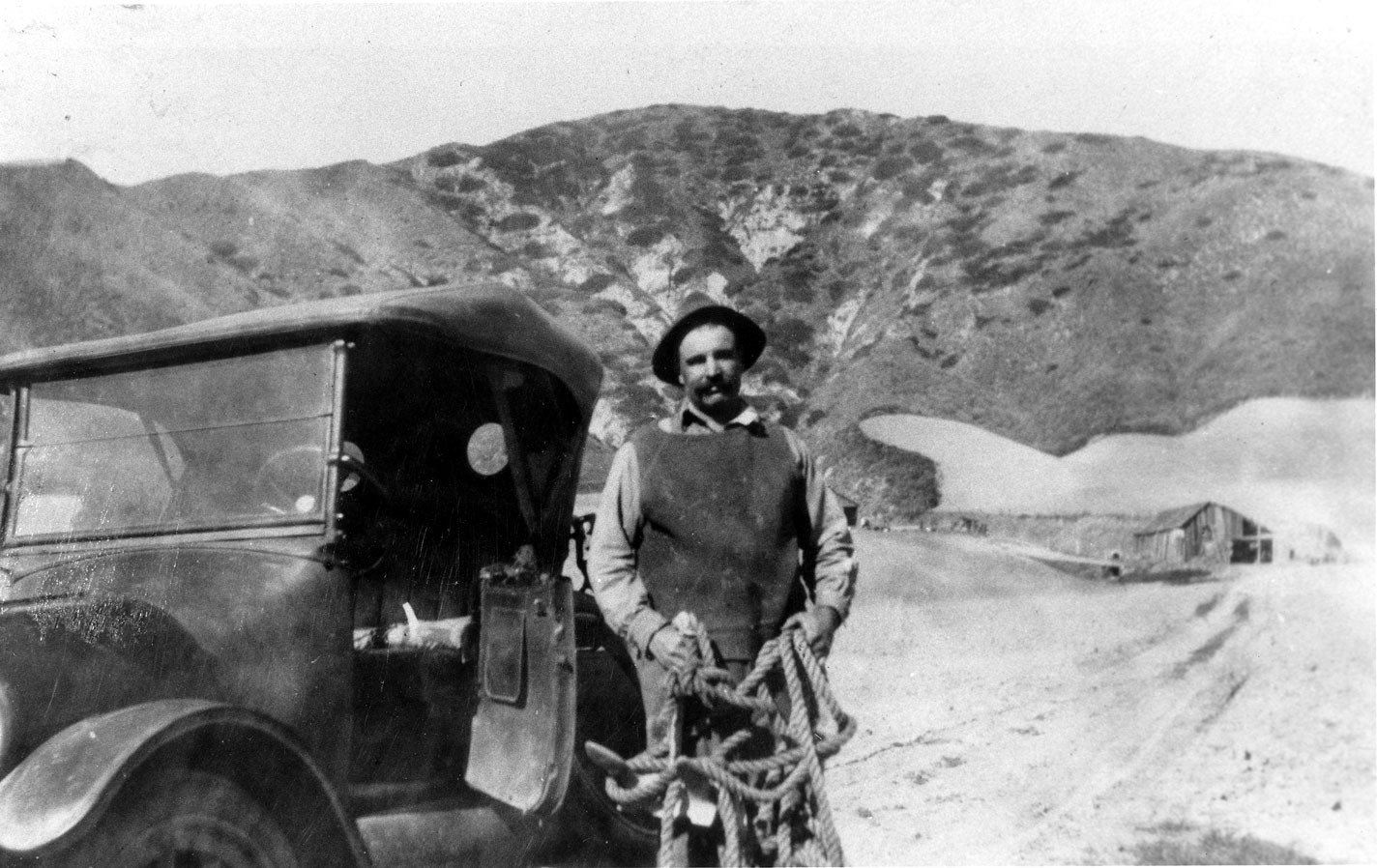

It all started in the early 1900s with the need for an easier transportation route between Ventura and Santa Barbara.

US Route 1 along the Northern Ventura coast toward Santa Barbara is one of the oldest and most historic overland corridors in California. It directly ties to the Spanish El Camino Real (The King’s Way) which served to connect the 21 Spanish California missions. In 1887 a railway was constructed in Ventura County with a service established from Ventura to Carpinteria. By the early 1900s, automobiles were introduced in Ventura and trade between the two regions grew as both cities developed. Driven by both the oil boom and the thriving commercial agriculture industry the coastal economies of both Ventura and Santa Barbara expanded.

This rapid growth fueled the need for a faster, more efficient transportation link between the two cities. The current travel methods by foot, horseback, and carriage along the beaches and coastal bluffs had a host of limitations. As crazy as it sounds, a ‘high tide’ presented a real barrier to travel during this period. Imagine having to wait six hours for the tide to change to get products to market.

The Rincon Causeway, built in 1912, changed the game. Travel between the two neighboring towns became not only easier but far more productive.

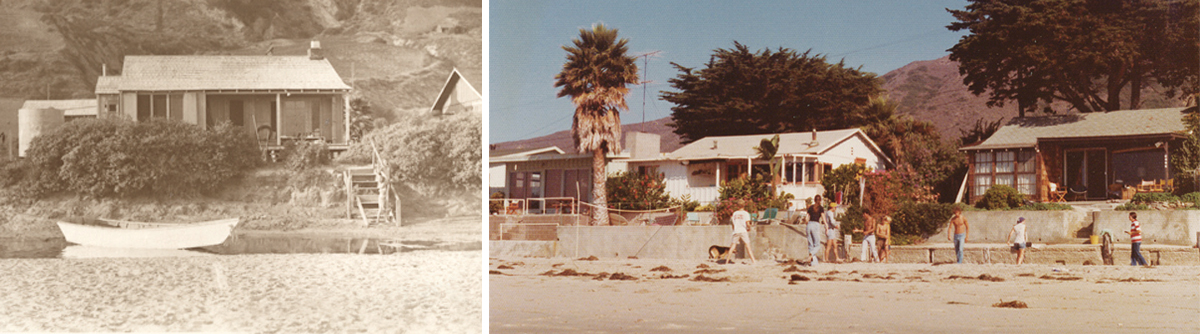

Around this same time, the Ventura County farmers and ranchers were starting to utilize the beaches for summertime recreation and to escape the heat of their inland farms. The advent of the “Beach Cabin” became a resource for Ventura County farming families that were allowed to “squat” or camp on farmland that ran from Ventura to Carpinteria.

The Need for Seawalls

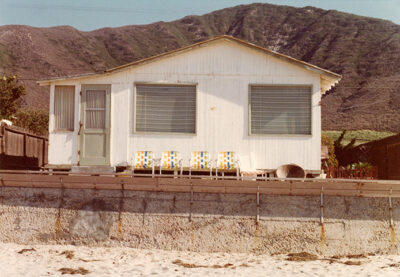

The original beach cabins were very basic. They had no running water and no electricity and were usually pieced together with found materials. Over time improvements were made to bring in both water and electricity. Naturally, families wanted to protect and preserve their investments in these cabins from the elements.

The original method for protecting land and structures from high tides and swells was a mixture of ice plants, rock, and wood. Ice plant originates from South Africa, and was brought to California in the early 1900s. The ice plant could withstand the harsh saltwater while holding the soil and sand base together for most higher tides. You can still see remnants of the original ice plant at some homes along the Faria and Solimar beach communities!

Around the late 1930s, the first wooden seawalls were built to replace the eroding ice plant banks. However, because the coastal land was predominately sitting on top of a shale base, there was continued erosion which undermined those structures.

Coastal Commission Permitted Seawalls

From the beginning up until the 1970’s seawalls were repaired and reconstructed as needed by the homeowners with cement block, wood, and rock. Then in 1976, the State Legislature passed the Coastal Act, which made the Coastal Commission a permanent agency with broad authority to regulate coastal development.

After the formation of the California Coastal Commission, coastal homeowners had to turn to them for the permitting process to get engineered seawalls designed and built to protect their properties. The Coastal Commission required lateral access to be given in exchange for the right to build. This only impacted beachgoers walking in front of seawalls and did not give permission for access across properties to the beach.

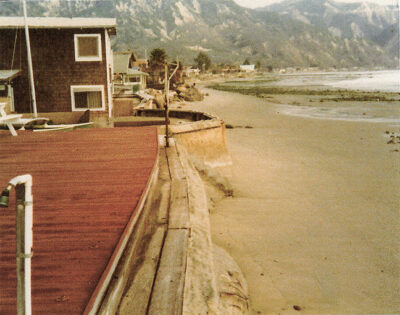

The Storms of 1983

The record-breaking El Nino spawned storms of late 1983 combined with extreme high tides inflicted a heavy beating on the central coast from Santa Barbara to Ventura. The series of storms lashed the coast creating substantial damage to 50 coastal homes from Santa Barbara to Ventura.

It was after this time that the ramp-up of seawall permits hit its stride. Local builder Ron Rasmussen remembers having six or seven seawalls in permit and construction following the 1983 storms.

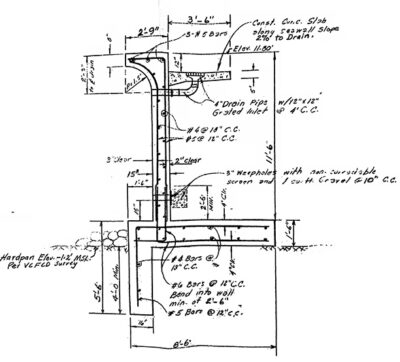

Most of these walls were built with cement and rebar. They were usually built four to six feet down into the clay base. The following drawing shows a seawall built in Faria with a footing four feet into the bedrock/clay base.

They would slot the footing into the shale four feet down and four to six feet in front. The challenge was to get the footing frame in place and ready to pour while you were fighting incoming high tides and water seeping into the box that framed the footing. Because of the high tides and surf, they had a six to seven-hour window to pour the concrete. Sometimes this dictated working in the middle of the night to get it completed. A typical seawall took two to three weeks from start to finish.

State Lands Commission Lease

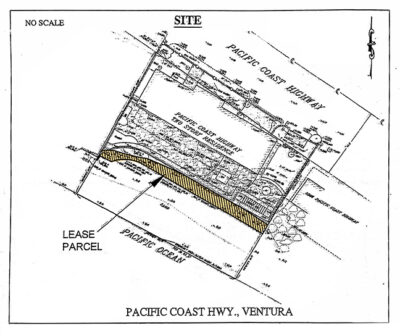

Protecting and preserving our treasured coastline while serving the needs of the government is a complicated balance. The government environmental program’s stance on seawalls has been to not allow them. One of the last seawalls to be engineered and permitted took place in the late 1990s. It required the owner to lease the land that was underneath the wall. Because of changes in the mean high tide line, the State’s position holds they own the land in front of coastal homes. The mechanism they have used to allow maintenance of existing structures allows the owners to lease the land from the California State Lands Commission. The leasing process typically extends years into the future and requires minimal lease payments as set by the State. Of course, the State of CA could change this process, but it is manageable for now. The Coastal Commission has only been able to require Lateral Public Access for passive recreation use even though they have always argued for public access perpendicular to the beach and through the privately held property.

You can see by the above that the State identified what portion of the seawall is sitting on state lands and is subject to a lease.

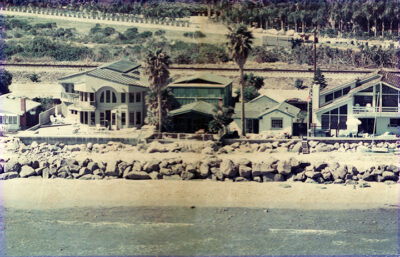

Seacliff Community Rock Revetment Maintenance

All during the mid-2000s, the Seacliff community had been embroiled in a lawsuit with the State Lands Commission (State of California) over the right to repair and maintain the rock revetment seawall that protects their homes along that stretch. After all, Caltrans had built the original wall to mitigate the impact on the coast after putting in the new freeway off-ramp. It was finally settled after a contentious negotiation over who owned the seawall and who has the right to maintain it. The State Lands Commission finally agreed to allow the homeowners to continue to maintain the structure and add rocks for the long term.

The Faria “Jetty”

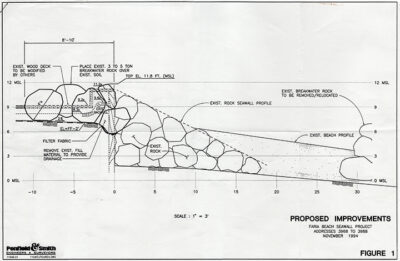

In the early 1990s six homeowners at Faria Beach collaborated and built a rock revetment in front of their homes. It didn’t take long for the Coastal Commission to come down hard on them to remove and mitigate any damage.

Most remembered how there was a sandy beach between the rock and the houses making it easy to navigate, but most would agree that this is not a viable solution. Ultimately, the owners were able to settle on moving the rocks back along their existing walls and to even get them permitted with properly engineered plans.

It should be noted that these plans are engineered and could provide a blueprint for less invasive rock revetments mirroring the placements at Solimar and Seacliff Beach Colonies. Those structures tend to provide a contiguous and consistent look as opposed to the baker’s dozen variety of seawalls now on display at Faria and elsewhere along the central coast.

Current day

Most seawalls and rock revetments along the coast are doing what they have done to protect homes for the last forty years. With the evolution of our municipality requirements and the balance of protecting and preserving our treasured coastline, it is important to know all the details and have a current understanding of our local seawalls

Understanding every lot, adjacent homes, and history of each seawall helps in how you potentially approach a sale or purchase, as well as being comfortable with your options for protecting your oceanfront home in the future. Like any good seawall, we need to be able to withstand the shifting tides and eventually, we’ll find the solutions.